WHAT IS GERD AND HOW DO WE ADDRESS THIS IN OUR PRACTICE?

Gastroesophageal Reflux (GER) is a common condition characterized by the rise of gastric contents into the esophagus. In healthy individuals, most gastric fluid is returned to the stomach by peristalsis stimulated by swallowing. While the remaining fluid is cleared by secondary peristalsis stimulated by direct contact of the gastric juices within the esophageal mucosa. In contrast, patients with GERD have delayed acid clearance, and the gastric acid and contents are involuntarily passed through the esophagus and into the oral cavity.

The cause of GERD is multifactorial, but the basic rationale is simple, that the body has an incompetent antireflux barriers at the gastroesophageal junction. It occurs when the contents of the stomach end up in the esophagus and oral cavity as a result of inadequate closure of the esophageal sphincters. Typical manifestations of GERD are heartburn, regurgitation, and dysphagia.

On this post, we will delve deeper in the common manifestation in the oral cavity, prevention and treatment of GERD.

DRY MOUTH OR XEROSTOMIA

Xerostomia is a major factor that risks the oral cavity for dental caries. Saliva is the primary medium of natural defense inside the mouth to get rid of threats to oral health. Saliva washes away contaminants and retains minerals so the minerals can be redeposited in the enamel when high pH conditions allow for it. In this way, it both acts as a tooth protector and a tooth strengthener. When dry mouth occurs, there can be too little saliva or none at all, or the saliva is thick and stringy. The mouth is left without its protective mechanism.

Dry mouth and GERD, unfortunately, have medication in common. GERD usually causes sufferers to use medication to manage their disorder. Medications for GERD frequently cause dry mouth in those who need medication daily. In fact, one small study found that a particular PPI, one of the most commonly prescribed types of medication for GERD sufferers, causes dry mouth that resolves when the medication is discontinued. The dry mouth in these was also found with other opportunistic oral infections of fungus or bacteria.

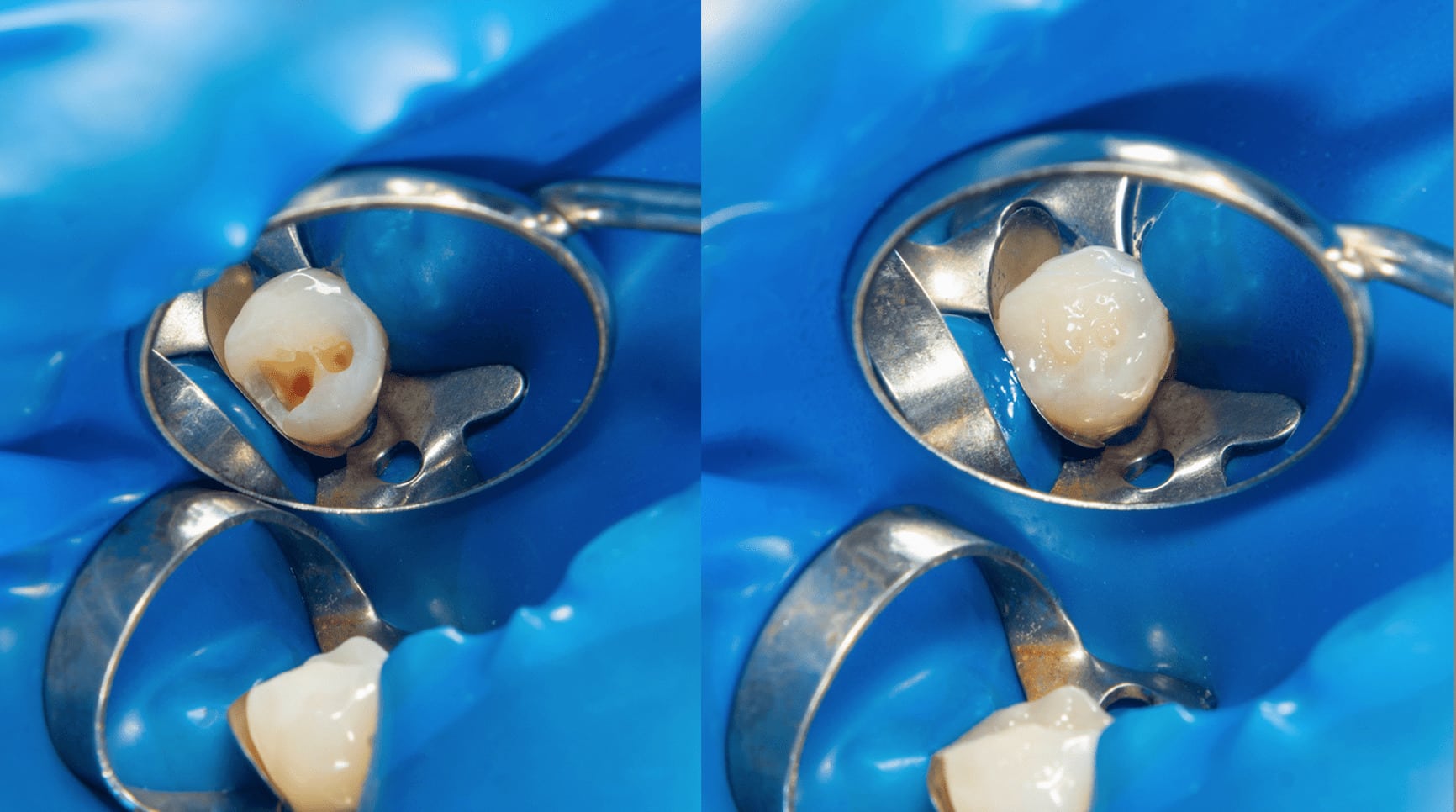

TOOTH EROSION OR CORROSION

Dental erosion described as tooth surface loss produced by chemical or electrolytic processes of non-bacterial origin, which usually involves acids. These acids can be endogenous or exogenous in nature. Endogenous(intrinsic) origins usually from regurgitated gastric juices while Exogenous (extrinsic) origin from usually dietary, medicinal, occupational and recreational sources

Chronic regurgitation of gastric acids in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease may cause dental erosion, which can lead in combination with attrition or bruxism to extensive loss of coronal tooth tissue.

The early detection of tooth erosion is important to prevent serious irreversible damage to dentition and requires adequate isolation of dried tooth surfaces and retraction of oral soft tissues, good lighting and a small mouth mirror.

The Affected Enamel Appears in the Following State:

➢ Smoothly glazed or “silky” with rounded surfaces, which may appear very clean because of the removal of stains, dental plaque and acquired dental pellicle by the gastric juice.

➢ Enamel thinning leading to an increased incisal and proximal translucency.

➢ Yellowish appearance of the teeth from “shine-through” of the underlying dentin due to demineralization.

➢ Presence of occlusal “cupping” of posterior cusp tips and anterior incisal edges, the thin unsupported enamel breaks off to leave jagged edges of the tooth.

➢ Sensitivity to change in temperature

BURNING MOUTH SYNDROME

It is a condition that causes a burning feeling in the oral cavity also known glossodynia, glossopyrosis and stomatopyrosis, in which a burning pain is experienced in the tongue or other oral mucous membranes. It can be associated with related symptoms, such as subjective xerostomia (dryness of the mouth) and dysgeusia (altered taste perception or a persistent bitter or metallic taste)

ORAL MUCOSAL LESIONS

Oral mucosal lesions may result from GERD by direct acid or acidic vapor contact in the oral cavity. Severe inflammations, such as erosion or ulcers, in the tongue, periodontitis, bilateral buccal mucosa and soft palate due to chronic exposure to acid

TREATMENT AND PREVENTION

The goals of treatment are reducing reflux, relieving symptoms, and preventing damage to the soft tissues and oral cavity.

I. Nonprescription (Over-the-Counter) Medications

A. Antacids

These medications are effective when taken one hour after meals and at bedtime because they neutralize acid already present. Some familiar brand names of antacids are Gaviscon, Kremil S and Mylanta. Some are combined with a foaming agent. Foam in the stomach apparently helps prevent acid from backing up into the esophagus.

B. Histamine-2 Receptor Blockers (H2-Blockers)

These drugs prevent acid production. H2-blockers are effective only if taken at least one hour before meals because they don’t affect acid that is already present. Common H2-blockers are Cimetidine (Tagamet), Famotidine (Pepcid), Ranitidine (Zantac), and Nizatidine (Axid).

If self-care and treatment with nonprescription medication do not work, prescribed antacids would be the next step.

II. Prescription Medications

A. Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs)

PPIs stop acid production more completely than H2-blockers. They block the production of an enzyme needed to produce stomach acid. PPIs include Omeprazole (Prilosec), Esomeprazole (Nexium), lansoprazole (Prevacid), Rabeprazole (Aciphex), and Pantoprazole (Protonix). Prilosec is now available over the counter.

B. Coating Agents

Sucralfate (Carafate) coats mucous membranes to provide an additional protective barrier against stomach acid.

C. Pro-Motility Agents

Pro-motility agents include Metoclopramide (Reglan, Clopra, Maxolon), Bethanechol (Duvoid, Urabeth, Urecholine), and Domperidone (Motilium). They help tighten the lower esophageal sphincter and promote faster emptying of the stomach.

III. Home Care for Patients

Refraining from eating three hours prior to bedtime. This allows the stomach to empty. Without food stimulation, the stomach’s hydrochloric acid production decreases.

➢ Avoiding lying down right after eating at any time of day. Elevation of the head six inches off of the bed. Gravity helps prevent reflux.

➢ Avoiding the ingestion of large meals. Eating a lot of food at one time increases the amount of acid needed to digest it. The alternative is to eat smaller, more frequent meals throughout the day.

➢ Avoiding fatty or greasy foods, chocolate, caffeine, mints or mint-flavored foods, spicy foods, citrus, and tomato-based foods. These foods decrease the competence of the lower esophageal sphincter.

➢ Avoiding alcohol ingestion. Alcohol increases the likelihood of acid reflux.

➢ Smoking cessation. Smoking weakens the lower esophageal sphincter and increases reflux.

➢ Losing excess weight. Overweight and obese people are much more likely to have bothersome reflux than people of healthy weight.

➢ Standing upright or sitting up straight and maintaining good posture. This helps food and acid pass through the stomach instead of backing up into the esophagus.

➢ Avoid the intake of certain medications such as over-the-counter pain relievers, including Aspirin, Ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin), or medicines for osteoporosis. These can aggravate reflux in some people.

RESTORATIVE OPTIONS OF GERD PATIENTS

I. Composite Restoration to protect exposed dentin and in surfaces susceptible to heavy loads. Always keep in mind the vulnerable surfaces --> unfilled resin or GIC

II. Orthodontic Extrusion and/or Prosthetic Restorations may be necessary if a large amount of dentin exposure and loss of vertical dimension:

➢ If there is vertical dimension loss (VDL) < 2mm → direct resin composite for incisal and palatal erosion

➢ If there is vertical dimension loss (VDL) 2-4mm → indirect porcelain laminate veneer and onlays

➢ If there is vertical dimension loss (VDL) > 4mm → indirect ceramic crowns/restos

➢ It is better to promote Zirconia crowns because of less prone to acid wear than resin composites.

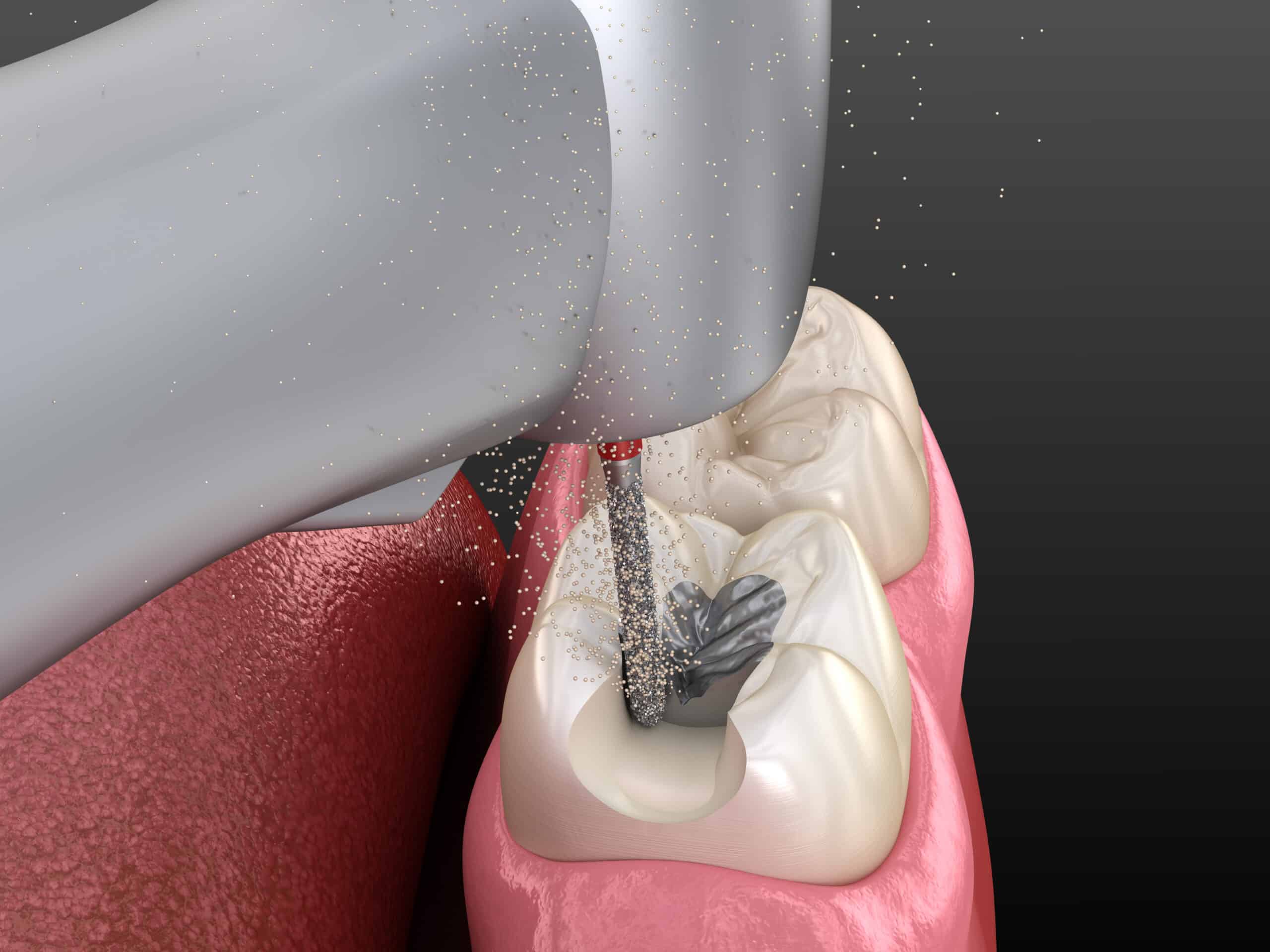

III. Proper Handling During Treatment of Patient

➢During treatment always assess risk of aspiration – diminish risk by using Rubber Dam, HV suction.

➢ Use saliva ejector underneath rubber dam to avoid aspiration.

➢ Regular communication with patient during procedure.

➢ Reduce water flow to high-speed hand piece; hand scale rather than ultrasonic scaling.

➢ When there is reflux while treating the patient, inform them to gargle with water, followed by rinsing with sodium bicarbonate, milk, or 0.2% NaF mouth rinse.

➢ Impressions: use fast setting materials; avoid excess material and avoid overfilling impression tray.

➢ Fabricating custom trays for daily/weekly at home fluoride treatments to supplement and help the teeth remineralized.

➢ Regular use of a 5,000-ppm fluoride toothpaste to supplement and help the teeth remineralized.

➢ Avoid prescribing aspirin and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for pain management, because they can contribute to reflux and exacerbate esophagitis. Instead prescribe Acetaminophen.

➢ Fabricate a bruxing (mouth guard) to limit the damage grinding will do on acid softened enamel.

➢ Appoint every 3-month recalls with application of concentrated topical fluoride.

➢ Ask for a medical clearance from a gastroenterologist for a definitive diagnosis and treatment.

➢ Prescribe antacids immediately after heartburn or sensation of acid reflux into the oral cavity.

➢ Avoid brushing for 30 minutes after acid exposure to allow salivary stabilization.

➢ Decrease the consumption of carbonated and acidic beverages.

➢ Prescribe the use of Xylitol chewing gum to stimulate salivary flow.

CONCLUSION

GERD is not something our patients should ignore and allow to remain untreated. It is our duty to encourage our patients to live a healthy lifestyle and have a nutritional diet. This will allow them to enjoy their life with a healthy and beautiful smile.

CONTRIBUTORS:

Dr. Bryan Anduiza - Writer

Dr. Mary Jean Villanueva - Editor